🧠 LONG article. The following is a personal piece on what it feels like to work with Jekyll in 2022, a brief exploration of static sites, and thoughts about Jekyll.

🔭 Article Scope: This article is written by a 20-something who spent most of his teens and early adulthood exclusively with PHP, Laravel, WordPress, and the LAMP stack. However, this 20-something has also been falling in love with Ruby. Totally not biased.

WordPress

I like WordPress. I’ve been using it since around 2012 and developing on it since 2015. There’s always been some elitist attitudes surrounding it in the web dev community. The greatest hits include: “it’s so slow”, “PHP sucks”, “it’s so bloated”, “it’s all site builders” ad infinitum. I’ve made my peace with it, it’s part of the job.

I don’t want to evangelize WordPress. While it’s robust, easy to set up, and extensible, there are a lot of things I don’t like about the platform. But, unfortunately, much of what I hear criticized is often a misconception, half truth, or just plain ol’ dislike of PHP.

Either way, my experience with it has taught me a lot, and has been (mostly) positive. I certainly wouldn’t know as much if I hadn’t been involved with it. There’s a very clear correlation between my knowledge about servers, the LAMP stack, and time spent with WordPress.

I still use it today, but mainly in a professional context. Around 2019 I started getting a little burn out since much of my work revolved around it. Over time, I began to feel like, yeah, maybe my rarely updated website doesn’t need a database. So I started to look elsewhere.

Static Sites, JAMStack, and Beyond

At a Glance

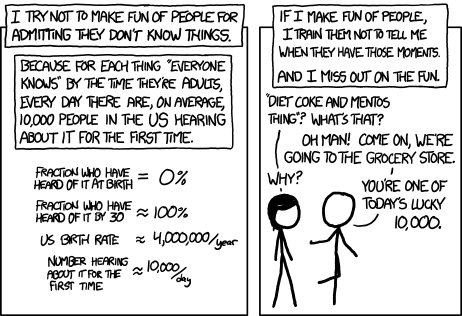

At this point, I hope Jekyll requires little introduction—but if you don’t know what it is, that’s okay! Consider yourself one of today’s lucky 10,000.

Jekyll was released in 2008, written in Ruby, and initially authored by GitHub co-founder Tom Preseton-Werner. For a long time, it was the site generator; sparking a passionate community of enthusiasts, evangelists, and developers. For many, it was their introduction to SSGs as a whole.

Since 2008, the landscape around static site generators has changed significantly. For one, there are now hundreds of them. jamstack.org currently lists 333, while staticsitegenerators.net lists 460. From Gatsby to Hugo to 11ty and beyond.

Jekyll, I’d argue, was the catalyst as to why there are so many. So while it may not enjoy the shiny new toy treatments other generators receive as of lately, its importance cannot be understated. It’s robust, tried, true, and most importantly—FUN!

Jekyll: The Premier Site Generator

Jekyll is a slightly opinionated static site generator. The opinion being that it treats blogging as a core concept in the site generation pipelines. E.g: in the default organizational taxonomy, a directory called _posts is generated where, you guessed it, posts go!

This doesn’t actually mean that you need to make a blog site with Jekyll. You are free to define custom collections—or taxonomies—and have quite a bit of flexibility as to how you can structure your site.

My Introduction

My introduction to Jekyll happened in the spring of 2017. A friend of mine was talking to me about Ruby on Rails and in one of the conversations, they mentioned Jekyll. I took a look at it, played with and…didn’t quite see what was special about it.

But, come 2019, I wanted to maintain my own website again. Until that point my site comprised a single HTML file. I wanted to make something larger and maintaining HTML without templating is just not something you should do anymore.

I thought about making my site in PHP, maybe with some framework, but that felt like overkill; I was trying to cut overhead after all.

Then, as if the fog had cleared, I remembered Jekyll. I began to read the docs again. This time it clicked. This is EXACTLY what I need

I’m not sure how to describe the feeling, but working with Jekyll gave me that I just made things happen on the browser feeling I got when I first started making website. It made things fun.

Due to…well, gestures at the state of the world, I put the site on hold until September 2021. But once I started, boy, did I start.

The Jekyll Confessional

I didn’t really plan out how I wanted to make my site. So, since I’m a millennial, I took a ✨YOLO✨ approach and made decisions based on the order that they appeared in my head.

What I did know is that I wanted to build as much of it as possible by myself.

Following this ethos, I decided on the following:

- No starting theme or template

- Accessible

- Bootstrap to speed up the design and structure

- Minimal use of external plugins because I wanted to learn new things

- Fast load times

- Auto-deployment on my own server

- Some sort of CMS

How do you install Jekyll in 2022?

I remember reading an article some time ago comparing various site generators; their pros, cons, etc. One con I remember seeing for Jekyll was that it had a confusing installation process.

Starting a Jekyll site seemed fairly straightforward to me. You make sure Ruby is installed, you install a few gems, you run: jekyll new . --blank to make a barebones Jekyll site. Then, you run bundle exec jekyll serve to start the web server/compile and finally—BAM! You have a bare-bones Jekyll site that you are now free to design to your heart’s desire…in theory.

Admittedly, articles like theirs (or mine) are subjective by nature, and of course, what might be easy for someone can be absolutely difficult for someone else. I do think the official documentation can get you there fairly painlessly…but the complexity I think lies in something less obvious.

Ruby Versions and Ruby Environments

Did you know a lot of operating systems have Ruby bundled already? MacOS ships with it. You can check if yours has it by running ruby -v in a terminal.

What I didn’t know is that my Linux distro, KDE Neon, had quite a few core components that had Ruby dependencies. Wanna know how I found out? I blindly followed a tutorial about upgrading your Ruby version, which ended up purging Ruby…and in turn ended up purging a bunch of my system’s core components. When did I realize this? After I had pressed enter.

Here are two things I learned (feel free to steal this for your LinkedIn feed; emphasize how this experience changed you as a person):

- I know better. I should know better than to blindly paste commands. But I did it because I was lazy and liability is fully on me. Thankfully (🥲), I’ve screwed up my OS in similar ways to this in the past and I know how to recover from them.

- However, if someone that doesn’t know better and just wants to get their version up to date (because they’re curious or because a tutorial said so); if they end up with a borked system, the tool will be tainted in their eyes.

I know there’s safeguards. I know I’m a tad dramatic; purging a language won’t make your system explode (usually.) I know in most cases “damage” will be fairly inconsequential. But I also know it’s easier to say “it’s your fault bro” than to provide a way to mitigate situations like this. I don’t subscribe to that mentality. If you don’t work with a technology extensively, the quirks of it will be unknown to you.

So what’s the solution in this case? Use rbenv. What does it do? It lets you install and run multiple versions of Ruby side by side. Below is the installation procedure I follow.

Remember, don’t blindly trust my commands! Always verify.

There we go! If you want to know more about how rbenv works, I highly encourage you to check out this guide.

I don’t want someone, especially beginners, to be afraid of Jekyll or Ruby because of a bad experience with the installation method. To Jekyll’s credit, their docs do mention Ruby version control; it’s just not in the forefront.

Though, I want to make it perfectly clear that this isn’t an issue with Ruby or Jekyll. This issue isn’t even exclusive to languages, rather related to documentation in software as a whole.

Overall, sometimes documentation will have to assume some level of knowledge. Speaking as a technical writer, it’s unrealistic to expect (especially for free/open-source software) to have documentation that aims at every skill level. I don’t have a clear solution but I do think that it’s important to consider technology quirks when writing guides.

Ruby Dependencies, Gems, and Bundler

For most Ruby-driven projects, Jekyll included, always use bundler and your Gemfile to manage dependencies. If you come from JavaScript, these two technologies work in a similar way that a package.json works in npm. They keep your dependencies in check and can help you avoid conflicts.

Also! If you followed Jekyll’s official documentation, you should remove your gems folder from your home directory, remove the PATH from your .bashrc or .bash_profile, and restart your shell.

That should take care of Ruby! As for Jekyll, you might need a few extra tools.

Newer Versions of Ruby

If you are running a version of Ruby 3.0 or higher with Jekyll, you will need to include another gem. On your current project run bundle add webrick. This will allow the local server to function properly.

Windows Specific Quirks

If you’re developing on the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL 2+), you’ll also need to serve your site from within the Linux subsystem (e.g, not from any directory in /mnt/c). If you don’t, auto-reload won’t work and if you have any JavaScript dependency managers, those will break too. This issue is not Jekyll specific, read more about it here.

Lastly…you might wanna alias bundle exec jekyll serve --force_polling --livereload in your .bashrc or .bash_aliases to serve your site. I have it set to jserver.

Time To Structure

Initially one of the things I spent the most time on was deciding how I should organize things and how I should design it. I spent a good amount of time visiting personal home pages, blogs, and folks on the indie web and their repos to get some ideas.

I settled on having only two layouts: one main wrapper (with two structures) and a layout for blog posts that inherits the main layout. In the early stages of the site I played around with the idea of having different layouts per page but with the (lack of) content I had so far, it didn’t make too much sense. I opted on using Bootstrap 5 since their grid system makes things really easy to structure.

I also went full on Liquid components and made components out of every little piece of markup; if I needed to repeat it more than one time, it’s going in the _includes directory. While initially tedious, it has made maintenance and debugging simple.

Lastly, I went back and forth on how I would use data files. They exist to make the separation of content and structure easier, but I still don’t think I’ve found a great way to standardize them on my site. They handle the links for my navigation menu but some also handle content for a handful of pages.

Liquid

Jekyll comes bundled with the Liquid templating language. The language is…interesting. It’s kinda programmatic. Reminds me a lot of erb syntax (which is probably intentional.) You can loop with it, it has variables, and most things function as objects.

The main draw for me was that I could break everything into a component and then import it into the page. You can also use liquid and external data files to create repetitive markup.

For example, making a menu will usually require a bunch of wrappers and links. With Liquid you can define the main structure and let Liquid take care of the rest; gathering the links from an external data file and building the rest of the structure via boilerplate.

You can use it to do some pretty advanced things. As mentioned previously, my site only uses two layouts. However, my main layout includes two different configurations: one with and one without a sidebar.

This is handled via if statements that check each page’s front matter at build time for the variable that enables or disables it. Pretty cool! In theory this means you could do it for more layouts on a single page but…I’d advise against it.

In addition, I also wrote an SEO-based plugin to handle the metadata. While the code is not pretty to read, it works and it’s flexible.

Design, Flare, and SASS!

Jekyll works with SASS right out of the box. All you need to do is put files within a _sass directory and import it within your asset folder’s main SCSS file.

My customization was fairly small—only importing the components I needed and tweaking existing variables. It ended up being fairly lean but it definitely looks like a Bootstrap site.

Bootstrap wasn’t meant to be a long-term solution anyway; it was mainly included for the sake of time. Right now the site is in a good place functionality-wise, so a redesign is around the corner!

Content Management

A few years ago I would’ve been fine writing my posts on Atom in markdown and editing the site’s metadata manually. Nowadays I’m more keen to the idea of having pretty front-end to facilitate the process.

I tried to look for a headless CMS solution that could help. I landed on NetlifyCMS. As far as content management goes, it ticked all the boxes. The only issue would be that if you wanted to use NetlifyCMS outside of Netlify, you’d need an authentication point.

Netlify is a great service, but unfortunately, my hosting is already taken care of. So I had to look into a way of setting up the end-point.

While there were a lot of community scripts seeking to facilitate the process, most of them were written in JavaScript. I didn’t really want to spin up a new server just for a Node app, so I researched further to see if there was a way to work with what I already had: a LAMP stack server. Comes to worse, I’d probably have to spend a weekend writing my own solution.

Fortunately, I didn’t have to write much! Oliver van Porten already had! I can’t thank him enough for this. Installation went without a hitch and in half an hour, I could authenticate.

Auto-Deployment 🚀

One of the most exciting prospects of modern web development to me is auto-deployments. Since I was coming from PHP-land where everything is “server-rendered” by proxy, it was an engaging exercise to think about how to handle the same prospect in the “static” world.

I explore several solutions (Travis CI, Render, self-hosted Netlify-like services) but ultimately opted for GitHub actions and a script:

Set up a GitHub Action

The action is quite simple:

- Runs on every push to main

- SSH (courtesy of `appleboy/[email protected].) into my server using a few secrets, then runs two commands

- The first commands enters into a directory

- The second command executes my build script

Deploy Script

The script essentially began as a git hook (found in .git/hooks/). The final product is a bash script which:

- Locally clones site repo

- Checks to see if dependencies are installed in the server, if not, it installs them.

- If they are installed, it sets the site environment to production, builds a local copy in a temporary directory.

- Clones temporary copy to the directory where the webserver is listening on.

Not that fancy! In the future I’d like to improve the script to catch errors. As it is, though, works just fine for what I need.

Complexity As a Form of Exercise

I gave myself many unneeded headaches while building this site. For example, making a tag and category page would be fairly easy had I used one of the many plugins that does it for you, such as Jekyll Archives.

Deciding not to use plugins didn’t come from a “I’m doing it all myself because I am an expert web dev, nyeh” mentality (I did end up using plugins for some things). From the very start of my journey in web dev, or programming as a whole, I tended to learn better if I just jumped on the deep end and tried to figure it out. The confusion to enlightenment pipeline, as I like to call it.

In the past few months that has certainly been true.

It has also been terrifying because I realized just how long I’ve been stuck on the back-end and how much the web has changed since 2017 (which was the year I began to mainly professionally work with WordPress.) There’s no shortage of things to learn. For me, the overwhelming thing isn’t what to learn, it’s more “dammit, I should probably stick with one thing for a while.”

Making things from the bottom-up has been super fulfilling and I wanna keep doing it.

Conclusions

It’s funny, this article has been stuck in draft mode since pretty much around the same time I started to work on the website. Since then, my preferences in web development have been changing; I have been overwhelmed with ideas, learning things, and exploring new venues. In short, this took longer than I expected!

The internal paradigm of what I want my site to be has changed significantly. From the tools I use to my ideas of what comprises “personal homepages”.

Content Management

What I wrote about NetlifyCMS still stands; it’s a great and simple CMS. However, for me, it has been getting a little tedious to keep up with the config changes. This is mainly my fault! I changed a lot of core components after I had already written the config.

For example, the SEO plugin I made used to work perfectly with NetlifyCMS. Last month I decided to refactor it. The current iteration isn’t integrated into NetlifyCMS because I would have to rewrite that part of the config again. I normally wouldn’t mind this but the NetlifyCMS config file is pretty linear (YAML).

To my knowledge, there’s no way to reuse similar config options. Which means I’d have to find the existing snippets of config relating to the SEO plugin and then replace them. This would be fine but my config right now is 310 lines of undocumented code with multiple levels of nesting.

The complexity is totally my fault, but I do wish it was easier to maintain.

I would still recommend it if you’re looking for a fast and easy headless CMS solution. Though, if you have the attention span of a pigeon like me, you might want to get your site as “finished” as you can before writing the config.

Ruby

Overall, working with Jekyll has been a joy and so much fun. In fact, Jekyll was in part responsible for my decision to give Ruby another chance. I’m happy to announce that I am going to purge all knowledge of WordPress and pivot into Rails development1. Later PHP 😎

In all seriousness, what didn’t click about Rails and Ruby as a language back in 2017 , now has. Writing Ruby is so much fun and I’m not sure if I can go back. Not to mention that the community is pretty darn great (one particular dude aside.)

Jekyll

Something I’ve yet to mention is the current state of Jekyll; mainly because it hasn’t been a relevant conversation point. I think it’s time to bring it up.

I was browsing the Jekyll Talk and I saw someone ponder about the future of Jekyll. To address it, you should know Jekyll is in an unofficial ‘soft’ maintenance mode2. While there are still commits and releases happening, feature-wise Jekyll seems to be at a standstill.

Is that a bad thing? In my opinion, not really. Jekyll is mature; when you spin up a new Jekyll site, you know what to expect. But, it’s quite possible that there will be a point where the features it offers might not be enough for your needs.

Common pain points I’ve come across online are that:

- it’s difficult to integrate different build systems,

- some people feel Jekyll is missing essential blog features at its core,

- and while there are a lot of plugins and themes, a good number of them are not maintained anymore.

The community is still alive. Things could be changed—but in open source it’s easier to talk about it.

I didn’t really need fancy features, but ultimately my interest in things like TypeScript and native web components made me feel like I should explore other SSGs.

I tried most of the popular ones but they didn’t really click the same way Jekyll had. That is, until I discovered Bridgetown.

Bridgetown

I had heard of Bridgetown a few months prior to the Jekyll Talk post I linked. I didn’t check it out until January. Something you’re bound to learn rather quickly is that Bridgetown was forked from Jekyll! With that said, this isn’t ‘Jekyll v2’. While its roots and DNA might stem from the same project, Bridgetown is its own thing.

In short, Bridgetown offers a familiar comfort and extends it beyond what I could imagine. The documentation is magnificent, the component workflow is very exciting, the community is very friendly, and I’m excited about its future as a full-stack framework. If Jekyll had nudged me to Ruby, Bridgetown flung me into the abyss.

Though, nothing is without obstacles. Something I had to get my head around is that Bridgetown is very opinionated about front-end building systems. This was confusing, but ultimately, it was just one more fun challenge to tackle.

I plan to dedicate an entire post to Bridgetown at a later date. At the time I’m writing this (2022-03-08 17:06:37), Bridgetown just had its 1.0 release. I was lucky enough to contribute some documentation and I’m looking forward to further my involvement.

In conclusion, I am a fanboy and plan to port this site over to Bridgetown in the next week. As short as my stay was with Jekyll, this isn’t a farewell. I still love Jekyll and I will continue to use it on a number of projects. Jekyll still has a very good place in this dynamic world and I’ll fight anyone that says otherwise.